Religious segregation in Northern Ireland schools

Northern Ireland is a nation with a traditionally conflicting religious identity. As is well known, strong tensions between Protestants and Catholics have affected the country for many years, resulting in violent armed conflicts that have claimed many lives.

At the origins of the conflict, the opposition between the mostly Protestant Unionist majority, wishing to remain part of the United Kingdom, and the nationalist minority, wishing to join the Republic of Ireland, fueled strong tensions between the two religious groups, leading to systematic discriminations of Catholics in a wide variety of contexts, from employment to the criminal justice system, housing allocation and electoral malpractices.

Tensions exploded in the late 1960s when Catholics opposed the discrimination by initiating a campaign that met strong resistance from Protestants and led to the breakdown of law and order and the re-emergence of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), a paramilitary organization with the stated aim of reuniting parts of the island under the banner of the Republic of Ireland.

The British army was sent in to restore order in 1969 and a few years later the government fell, and the Northern Ireland parliament was dissolved by the British government, which regained control of the territory. The violence, however, continued until 1998, when the signing of the Belfast Agreement, also known as the Good Friday Agreement, established that Northern Ireland would remain part of the United Kingdom, as long as the majority of Northern Irish citizens so wished.

The commitment to the creation of proportional, cooperative, and consensual institutions convinced the paramilitary forces to end their campaigns, which had led to the deaths of more than 3.000 people. However, despite the peace agreement, Northern Ireland continues to be divided due to the educational, housing, and social barriers between religious groups that make up and divide a society that has not yet adapted to the new reality of peace.

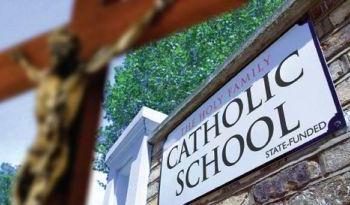

The context in which, more than any other, segregationist tension is still clearly discernible is the school environment, which has long been (and still is) characterized by significant segregation of students according to their religious affiliation. Children from Catholic families attend schools run by the Catholic Church, while Protestant children attend the so-called “controlled schools” that, although under state control and management, maintain strong links with evangelist churches.

The Education Reform Order of 1989 also introduced a new category of schools: integrated schools, whose main objective was to provide a religiously mixed environment able to attract a reasonable number of both Catholic and Protestant pupils. However, rather than moving towards the construction of this new category of schools, the government opted for the gradual conversion of the existing schools into integrated schools, which came about only marginally.

In Northern Irish schools, religious instruction is linked to the denominational origin of the schools themselves. While in Catholic schools denominational teaching is transmitted, in the controlled schools, which are now, in fact, public schools, the teaching of religion is based on the Holy Scriptures and marked by the transmission of the values of the Christian religion. In this way, it is evident not only that it is difficult to foster real integration in public schools between Catholic and Protestant children, but also to allow the inclusion of students with a different religious belief and from atheist families.

This system is far removed from the model of objective, neutral, pluralistic teaching that the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights has repeatedly considered to be the only one consistent with the provisions of the Convention (in particular with the right to religious freedom and the right of parents to educate their children according to their own philosophical and religious convictions).

From the case of Folgero and others v. Norway, to the more recent Papageorgiou and others v. Greece, the Strasbourg Court has always identified indoctrination as the insuperable limit for the contracting States, albeit endowed with a wide margin of appreciation, in organizing school curricula and the teaching of religion in public schools. The absence of any ideological imposition in religious instruction in state schools would only be granted by lessons aimed at providing knowledge about religion in an objective and neutral manner and not at transmitting the values of a particular religion by presenting them as absolute truth.

In this national and supranational context, the Supreme Court of Northern Ireland has recently intervened, noting the need for a reconsideration of the basic curriculum and legislation on the teaching of religion, clarifying, in particular, that the Department of Education should ensure that the provisions for the teaching of religious education, and of the Christian religion in particular, in Northern Ireland comply with the provisions of Article 2P1 and Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

The need to comply with supranational standards and with the indications coming from ECtHR jurisprudence is significantly influencing the direction of Northern Ireland's jurisprudence and legislation. The problem of religious education, which ends up leading to school segregation of students based on their beliefs, dragging on a conflict that has become entrenched in Northern Irish society, may finally be on the way to being resolved.

(Focus by Nadia Sima Spadaro)

Essential Bibliography:

D. Akenson, Education and Enmity, the control of schooling in Northern Ireland 1920-50, London, 2011, 103 e ss.

D. Armstrong, Schooling, the Protestant churches and the state in Northern Ireland: a tension resolved, in Journal of beliefs and values, vol. 38, 2017, 89-104.

P. Barnes, The character of Controlled schools in Northern Ireland: A complementary perspective to that of Gracie and Brown, in International Journal of Christianity and Education, 2021, 337 e ss.

G. Byrne, P. Mckeown, Schooling, the churches and the state in Northern Ireland: a continuing tension?, in Research papers in education, 1998, 319 e ss.

J. Darby, Conflict in Northern Ireland: a background essay, in S. Dunn, ed, Facets of the conflict in Northern Ireland, London 1995, 15 e ss.

A. Gracie, A.W. Brown, Controlled schools in Northern Ireland – de facto protestant or de facto secular?, in International Journal of Christianity and Education, 2019, 349 e ss.

S.J. McGuinness, Education Policy in Northern Ireland: a Review, in Italian Journal of sociology of education, 1, 2012, 205 e ss.

K. Schiaparelli, Divided society, divided schools, divided lives: the role of education in creating social cohesion in Northern Ireland, in Clocks and clouds, 2015, vol. 6, n. 1, 1 e ss.